What is success?

What is power?

What is real power?

Is it the ability to control others, to force them to bend to your will? Or is that really just a kind of fear in disguise? Because to me, real power is something else. It’s the power to change yourself. To grow. To stop performing. To break a pattern that’s been quietly wrecking you for years. That’s power.

And success, how do you define that? How am I supposed to know if I’m successful? Whose rules am I following?

Because if the rules are made by people already in power — the wealthy, the connected, the ones who’ve built the system in their image — then those rules don’t reflect my interests. They weren’t designed to.

I wrote more about this mismatch between systems and individuals in Dispatch One: Misunderstood by Design.

What is success in the workplace?

We’re told it’s the reward for hard work, loyalty, talent. But it often looks more like a lottery. And lotteries only work if most people don’t win. That’s the whole point. If everyone gets the prize, it’s not a prize anymore, it’s a refund.

So when the system says, “Do these steps and you’ll be successful,” it’s rarely about personal growth or truth. It’s about fitting in. Compliance. Say the right things. Present the right way. Don’t challenge anything too loudly.

And people do this. They bend. They mould themselves to fit into a shape they never chose. And what do they give up in the process? Time. Health. Integrity. Family. A sense of who they are.

Because if success means becoming someone you’re not just to be accepted, then I don’t think that’s success at all.

I’ve worked full-time in the Australian Public Service since 1997. I’ve seen people “ascend” to the EL1 and above levels. And I’ve watched how they change. Not because they’re bad people, but because the expectations change. The pressures change. The cost changes.

I explored how people adapt to survive in systems that expect constant performance in Dispatch Five: The Art of Masking.

Some fight hard to get there. And then, once they’ve made it, they turn around and make sure it’s harder for anyone else to follow. I’ve seen how the system protects itself — how it filters people. It keeps the ones who align. It spits out the ones who don’t. Those who question, who speak plainly, who don’t perform the right way — they burn out. Or they get quiet enough to survive, but they never rise.

On a few rare occasions, I’ve seen someone reach EL1 and then step back to APS6. And unless you’ve worked in the service, you might not realise what a big deal that is. EL1 is the first executive level. APS6 is the highest of the regular classifications — the last level where you still have a bit of autonomy. Some breathing room. You can still prioritise your health, your family, your sanity. But once you cross that line into executive roles, you’re expected to prioritise the job above everything else. You might not be told directly, but it’s clear.

I’ve never doubted I could perform at that level. But I’ve always known I wouldn’t enjoy it. And I’ve always said: when my employer comes over after work and helps me mow my lawn for free, then I’ll work back late for free. Until then, no.

Good corporate citizen?

Even the word corporate — what does it actually mean?

It comes from corporatus, the past participle of corporare, meaning to form into a body. So when someone tells you to be a good corporate citizen, they’re asking you to serve an imaginary entity. A fictional body. A construct.

It’s not even a person. It doesn’t feel pain. It doesn’t age. And the people who designed its rules and measures may not even be part of it anymore. Sometimes we’ve lost track of the purpose behind the rules altogether. Yet we still serve them. Sometimes fiercely. Sometimes without question.

It reminded me of the kind of institutional optimism I pushed back against in Dispatch Four: The Tyranny of Positivity.

I don’t believe in it. I’m an atheist when it comes to corporations.

To me, it’s just a set of instructions. A machine, designed to get people working in a particular way, towards goals they didn’t choose, measured by metrics they didn’t set. It’s not something I’m going to serve.

Work is a means to an end. For me, that end has been to feed my family, put a roof over our heads, and — if possible — set myself up to avoid poverty in old age. That’s it. And I hope that when I do eventually go, I go peacefully, in my sleep. That’s the extent of my ambition.

Time, Pink Floyd, and perspective

I’ve been a lifelong — quite literally — Pink Floyd listener. I’m 58 now, and I’ve been listening to them since I was about 11.

We didn’t have the internet. No social media commentary. We had our albums, our rooms, our cassette decks. And we had the space to make up our own minds.

It’s only in more recent years that I’ve started reflecting more seriously on the lyrics. That’s common — I think most of us do that as we age. We go back to the things that shaped us and see them differently.

For me, it’s The Dark Side of the Moon. Especially the track Time.

Now to be clear, it’s not my favourite Floyd album. That would be Wish You Were Here. And my favourite song — by far — is Shine On You Crazy Diamond. All parts of it. If my understanding of Syd Barrett is even close to accurate, that track may well be a celebration of neurodiversity. And a lament for how society discards the people it doesn’t understand.

But Time is a track people know. And it fits what I’m trying to reflect on here.

A lot of people hear Time as a motivational wake-up call — a nudge to get moving and accomplish more. But I don’t hear that.

The regrets people mention when they talk about the song usually sound like corporate milestones. Promotions. Money. Status. As if those were the only markers of meaning. That tells me how deeply those ideas have taken hold.

Maybe this is one of the benefits of having autism and ADHD — at least in my experience. Even if I wanted to fully absorb those expectations, I don’t seem to be able to. I can play the game for short stretches, but eventually something in me pulls away.

And I’ve long had the feeling that autism and ADHD might not be flaws or disorders at all. Maybe they’re evolutionary tactics. A kind of failsafe — something baked into humanity to resist complete assimilation.

That thread — about difference as resistance — came through strongly in Dispatch Six: A Future Without Masking.

When I hear Time, I don’t hear a call to push harder. I hear a warning. Not that you haven’t done enough — but that you’ve been doing too much of the wrong thing.

That while you’re aiming at something out there, you’re missing what’s right here.

What matters

There are thousands of books out there that try to tell people how to be successful. Some are grounded. Some are absurd. But most of them share a hidden message: that if you just do what they did, you’ll get what they got.

Only, you won’t. Because your life isn’t theirs. And for them, your success isn’t really the point.

Their success is.

That doesn’t make you a failure. It means you’re not the product.

I’m not saying all executives are bad. I’m not even saying most of them are. But I do question why someone would want to be at the very top of anything. That kind of ambition isn’t neutral. It shapes what you see, what you tolerate, what you value.

And I’ve always found it insulting when people like that look down on others for lacking ambition — as if ambition only counts if it serves a structure.

I have ambition. I’m writing this, aren’t I?

That tells you I believe I have something worth saying. But I don’t pretend this is the ultimate answer. These are reflections. But I do think I’m getting close to something real. Something that matters.

And I don’t like what I see.

Narrative, truth, and old systems

It reminds me how much of what we do is driven by narrative. Stories have power. And we’re given those stories early. About success. About ambition. About worth. And we accept them — because that’s how human brains work.

But once you start looking beneath the story, you can’t stop. At first it takes effort. Then it becomes habit. Eventually it’s effortless — and the effort shifts to dealing with people who haven’t made that shift yet. You lose some of them. That’s just how it goes.

It’s important to be true to yourself. And to me, that means something very specific.

It means seeking to understand who you are. Not arriving at an answer — but asking the question for your whole life. I’ve often had to grow in one area before I could come back and finally see what another part of my life had really been about. What a belief system was doing to me. What an experience really meant.

And for most of us, I think, the systems in the background — society, politics, religion — they just seem like the landscape. The hills in the distance. The ocean. Always there. Permanent.

But with time, I came to realise they’re not mountains.

They’re built. They’re constructed. And they can be changed.

One possibility

I’m not offering a solution. But I am pointing to one possibility.

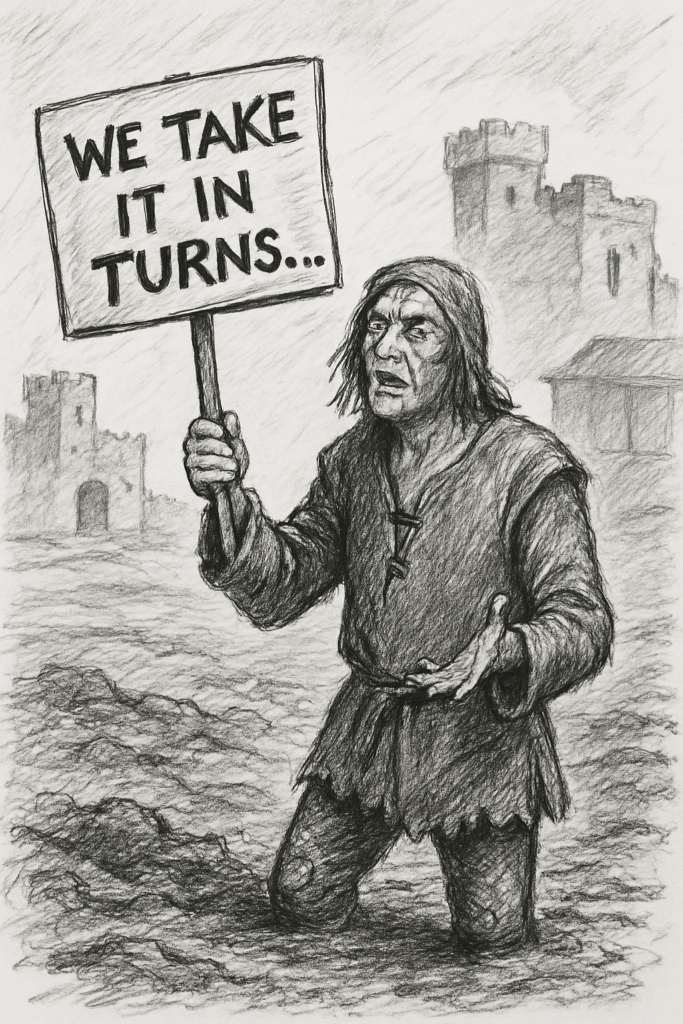

Let’s go back to Monty Python — The Holy Grail.

Dennis the Peasant. Covered in mud. Explaining:

“We’re an anarcho-syndicalist commune. We take it in turns to act as a sort of executive officer for the week… but all the decisions of that officer have to be ratified at a special bi-weekly meeting…”

It sounds ridiculous, but there’s something there. Shared responsibility. Rotating leadership. Power that’s granted, not assumed.

Maybe that’s not the answer. But it’s an answer.

Because the point isn’t to climb the system.

It’s to ask whether the system was ever really serving us at all.

Endnotes

- Pink Floyd’s Time was written by Roger Waters and released on The Dark Side of the Moon (1973). In interviews, Waters has described the song as a reflection of reaching adulthood and suddenly realising time had already passed — not a call to “achieve more,” but to recognise how easy it is to sleepwalk through life.

- Shine On You Crazy Diamond, from Wish You Were Here (1975), is widely interpreted as a tribute to Syd Barrett, and is often read as a lament for how the music industry and society at large treat those who don’t conform.

If you found this reflection valuable, you can support my writing here:

👉 Buy Me a Coffee